(Part of the Shadowfax Author Series: Writers on Writing)

by S. T. Finn

Appreciated and practiced throughout the world, haiku evolved in feudal Japan when it was separated from the opening verse of a longer, linked poem known as renga.

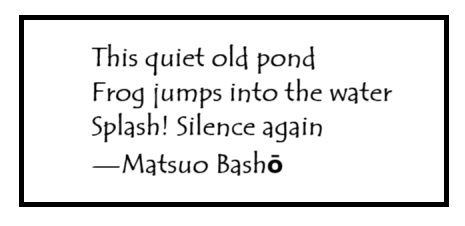

Traditionally, haiku is a three-line poem about a single moment in time that also offers a glimpse of the eternal. Each haiku typically includes a kireji (“cutting word”) and a kigo (seasonal reference).

It’s also the shortest form of poetry in the world. But rather than adhering to the often translated (and arguably misunderstood) concept of containing “only seventeen English syllables” (in 5/7/5 structure), English-speakers should appreciate that Japanese haiku uses onja (“syllable-sounds”).

Onja are often shorter than many one-syllable English words. Consider the time it takes to say “me” or “to” as compared with “wrought” or “bright” or “through.” A slight difference, perhaps, but noticeable in such a short poem.

Japanese haiku is typically spoken in a single breath, where in English, speaking a haiku with the 5/7/5 structure can be difficult to speak aloud in a single breath. A more proper understanding might be to adhere to the “right” amount of syllables—whether it is 5/7/5, or 4/6/4, or even 3/5/3, as many English-speaking haiku poets now use.

Poems can “imply” an adherence to syllable count, striving for the right “feel” rather than anything numerically contrived, as well as being a seasonally based poem that compares or contrasts two subjects or objects, without being overly subjective.

What else makes a poem Haiku?

The Basic Rules of Haiku

Overall, haiku should illustrate the uniqueness of a single moment in place and time. Each poem should present a pair of contrasting images, one suggestive of time and place, the other a vivid but fleeting observation.

Each haiku should contain a dualism—the near and the far, foreground and background, sound and silence, temporality and eternity—showing the uniqueness of a single thing as well as showing the universality or inter-connectedness of all things. It should strive to express Eternity in a Moment, the Universe in a Particle.

Haiku must not judge or offer opinions and interpretations. Haiku must present things just as they are.

The best haiku uses concrete ideas and observations, things we can touch, see, hear, taste, smell—nothing abstract. No metaphors. No direct expression of love, hate, sadness, or feelings. Such things are left for reflective poets. But the best haiku can evoke powerful emotions in the reader.

It is said that haiku is not just something we compose; it is something we discover. Something we do.

Haiku is a presentation of how we perceive or experience something truly as it is, in a single moment—transient, dependent, and fleeting, as well as wondrous, awe-inspiring, and joyful. It is often about this ephemeral nature of reality and the inter-connectedness of all things.

Many haiku have a sense of Beauty in Nature often combined with a feeling of deep sadness or loneliness, exposing the transient nature of reality and the inherent suffering of all beings. But the poet must never separate from the experience or be reflective about it. Haiku poets seek nonseparation.

Like most things in life, few haiku poems achieve perfection. Some haiku may not even meet all the basic requirements. But the continued practice of haiku can help us deepen our appreciation of Nature and our place in the universe.

Writing and reading haiku encourages us to see the potential in each moment for profound appreciation and realization.

Ready to See For Yourself?

If you haven’t tried yet, compose some haiku for yourself … and discover the joy in just appreciating things, in and of themselves, exactly as they are in the moment.

The moment is there for you, after all. Embrace it.

now that winter’s gone,

the wind shares the open sky

with returning geese

—S. T. Finn

S. T. Finn lived and practiced in a Zen monastery for years and had a dozen haiku published in magazines and literary journals, including FROGPOND and MODERN HAIKU. Currently, he lives (and writes) on a forested mountain by a stream in New York State.

Interested in reading some haiku by the author?

A COLLECTION OF HAIKU in TWO VOLUMES by S. T. Finn

(both volumes of Haiku Travels include photography by the Author)

© copyright 2025 by Shadowfax Books