An Exploration of Superhero Diversity and Representation

by S. T. FinnIf you’ve always wanted to learn more about comic book history, the balance (or imbalance) of gender readership, and the legacy of under-representation, dive in.

This 10-Part article provides a glimpse into pioneering trailblazers, important first appearances, and the evolution of under-representation in comics.

Part 1 lays the groundwork and sets up our Superhero Criteria.

Part 2 examines the beginning of superheroes (and their predecessors).

Part 3 delves into changing readership imbalances and the romance genre.

Part 4 honors first appearances of important female superheroes.

Part 5 appreciates trailblazing female BIPOC superheroes

Part 6 presents important first appearances of Black superheroes.

Part 7 explores Asian, Hispanic/Latino, and Native American superheroes.

Part 8 celebrates first appearances of superheroes with disabilities.

Part 9 looks at the first gay, lesbian, trans, and nonbinary superheroes.

Part 10 brings it all to a dramatic conclusion.

NOTE: As we discussed in Part 1 , for the purposes of this article, a superhero is defined as a crime-fighter who fights for justice, and MAY have a mask, cape, or costume, and/or a secret identity, but MUST possess at least one of the following: 1) a special, peak-human, or unnatural skill or talent; 2) unique tech/gadgets used for crime-fighting; 3) a supernatural ability of some kind; OR 4) an actual super-power.

ALSO, if a hero does not possess a superpower, our Superhero Criteria stipulates that supernatural abilities MUST exist somewhere in the fictional universe for the hero to be considered a superhero (otherwise, they are “simply” a hero, vigilante, or crime-fighter).

With some exceptions, this article focuses mainly on mainstream American comics.

Part 3: A Romantic Aside

The comic book industry has experienced many ups and downs throughout its long history (including a near implosion and the bankruptcy of Marvel in the 1990s). But comics were not always about the heroes.

Pre-1950, hundreds of science-fiction, humor, horror, sports, and romance titles existed—and many sold in the millions.

Before the 1950s, comic books were marketed to either boys OR girls. But contrary to popular belief, the most voracious consumers of comic books were girls and young women.

Primarily in the 1930s, and for much of the 1940s, girls typically read anthologies that repackaged popular comic strips from newspapers, as well as standalone adventures or humorous comic strips that featured female leads. These early comics often focused on themes of independence, fashion, domestic life, romance, or “career girls.”

In the 1940s and early 1950s, some comics were read equally by both genders—with females still outnumbering males in readership in one very lucrative area.

Romance comics exploded in popularity in the late 1940s as the post-war audience shifted away from the first wave of Golden Age superheroes into other genres.

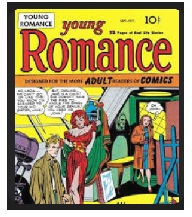

The first big sensation was Young Romance #1 (September 1947) from the writer/artist team of Joe Simon and Jack Kirby (who had created Captain America and Bucky Barnes about seven years earlier).

Young Romance is generally credited as the title that launched the popular romance comic book genre—followed by Young Love, Sweethearts, Heart Th robs, etc.

These extremely popular romance comic books focused on tales of love and jealousy, and featured emotional struggles from more of an adult perspective. They quickly became a major, million-copy-a-month industry.

Boys began to read more comics than girls only after the mid-1950s, particularly after the implementation of the Comics Code in 1954 (which was created by the Comics Magazine Association of America as a way to avoid moral regulation by the American government—and to counter perceptions of homosexuality in comics; see Part 9).

After the Comic Code’s crackdown (on horror and romance comics in particular), comic book publishers began to pivot even more toward superhero titles aimed at young males.

After this point, most superhero comics were written to and for boys.

Lacking in Diversity

It would be difficult to guess whether under-representation in comic books became a part of the industry preference or audience preference, as the industry seemed to assume that girls primarily wanted to read romance comic books.

But what comes first: Supply or demand?

Comics are created for those who buy them, after all.

Throughout the past century, there have been many unsuccessful attempts to create and

provide more diversity, attempts that often failed because not enough people bought (or continued buying) the comics.

(So, it’s always important to support creators and characters we believe in!)

Who Reads Comic Books Anyway?

After decades of leaning mostly male, comic book readership today is returning to a more equally balanced ratio. Recent studies indicate that women make up nearly 45% of the total comic book audience.

By contrast, a 1995 survey showed female readership had dropped to 13 percent (right before Marvel declared bankruptcy). A significant surge in female readership occurred by 2013–2014, when research indicated roughly 30%–45% of consumers were female.

Note that this is right after the release of major blockbuster movies from the X-Men, Batman, and Spider-Man franchises, along with the MCU’s Iron-Man, Captain America, Avengers, and Guardians of the Galaxy, as well as the TV show Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.—all of which helped to usher in rising interest in superheroes and brought more diversity into the comic book world.

In general, this impressive rise in female readership coincides directly with a growing demand for diverse characters and stories (and growing representation in movies/TV shows).

The audience demanded and the industry provided (and profited—big time).

And that leads us to our next segment…

For more milestones in comic books, check out Part 4, where we explore vital first appearances of female superheroes.

A lifelong collector of comic books, S. T. Finn is an author and artist who lives in a cabin in the Catskill Mountains. His stories and artwork can be found at ShadowfaxBooks.com.